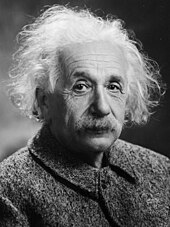

Albert Einstein (2)

Refugee status

Landing card for Einstein's 26 May 1933 arrival in Dover, England from Ostend, Belgium, enroute to Oxford

Landing card for Einstein's 26 May 1933 arrival in Dover, England from Ostend, Belgium, enroute to Oxford

In April 1933, Einstein discovered that the new German government had passed laws barring Jews from holding any official positions, including teaching at universities.[128] Historian Gerald Holton describes how, with "virtually no audible protest being raised by their colleagues", thousands of Jewish scientists were suddenly forced to give up their university positions and their names were removed from the rolls of institutions where they were employed.[130]

A month later, Einstein's works were among those targeted by the German Student Union in the Nazi book burnings, with Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels proclaiming, "Jewish intellectualism is dead."[128] One German magazine included him in a list of enemies of the German regime with the phrase, "not yet hanged", offering a $5,000 bounty on his head.[128][131] In a subsequent letter to physicist and friend Max Born, who had already emigrated from Germany to England, Einstein wrote, "... I must confess that the degree of their brutality and cowardice came as something of a surprise."[128] After moving to the US, he described the book burnings as a "spontaneous emotional outburst" by those who "shun popular enlightenment", and "more than anything else in the world, fear the influence of men of intellectual independence".[132]

Einstein was now without a permanent home, unsure where he would live and work, and equally worried about the fate of countless other scientists still in Germany. Aided by the Academic Assistance Council, founded in April 1933 by British Liberal politician William Beveridge to help academics escape Nazi persecution, Einstein was able to leave Germany.[133] He rented a house in De Haan, Belgium, where he lived for a few months. In late July 1933, he visited England for about six weeks at the invitation of the British Member of Parliament Commander Oliver Locker-Lampson, who had become friends with him in the preceding years.[134] Locker-Lampson invited him to stay near his Cromer home in a secluded wooden cabin on Roughton Heath in the Parish of Roughton, Norfolk. To protect Einstein, Locker-Lampson had two bodyguards watch over him; a photo of them carrying shotguns and guarding Einstein was published in the Daily Herald on 24 July 1933.[135][136]

Locker-Lampson took Einstein to meet Winston Churchill at his home, and later, Austen Chamberlain and former Prime Minister Lloyd George.[137] Einstein asked them to help bring Jewish scientists out of Germany. British historian Martin Gilbert notes that Churchill responded immediately, and sent his friend, physicist Frederick Lindemann, to Germany to seek out Jewish scientists and place them in British universities.[138] Churchill later observed that as a result of Germany having driven the Jews out, they had lowered their "technical standards" and put the Allies' technology ahead of theirs.[138]

Einstein later contacted leaders of other nations, including Turkey's Prime Minister, İsmet İnönü, to whom he wrote in September 1933 requesting placement of unemployed German-Jewish scientists. As a result of Einstein's letter, Jewish invitees to Turkey eventually totaled over "1,000 saved individuals".[139]

Locker-Lampson also submitted a bill to parliament to extend British citizenship to Einstein, during which period Einstein made a number of public appearances describing the crisis brewing in Europe.[140] In one of his speeches he denounced Germany's treatment of Jews, while at the same time he introduced a bill promoting Jewish citizenship in Palestine, as they were being denied citizenship elsewhere.[141] In his speech he described Einstein as a "citizen of the world" who should be offered a temporary shelter in the UK.[note 3][142] Both bills failed, however, and Einstein then accepted an earlier offer from the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, New Jersey, US, to become a resident scholar.[140]

Resident scholar at the Institute for Advanced Study

Portrait of Einstein taken in 1935 at Princeton

Portrait of Einstein taken in 1935 at Princeton

On 3 October 1933, Einstein delivered a speech on the importance of academic freedom before a packed audience at the Royal Albert Hall in London, with The Times reporting he was wildly cheered throughout.[133] Four days later he returned to the US and took up a position at the Institute for Advanced Study,[140][143] noted for having become a refuge for scientists fleeing Nazi Germany.[144] At the time, most American universities, including Harvard, Princeton and Yale, had minimal or no Jewish faculty or students, as a result of their Jewish quotas, which lasted until the late 1940s.[144]

Einstein was still undecided on his future. He had offers from several European universities, including Christ Church, Oxford, where he stayed for three short periods between May 1931 and June 1933 and was offered a five-year research fellowship (called a "studentship" at Christ Church),[145][146] but in 1935, he arrived at the decision to remain permanently in the United States and apply for citizenship.[140][147]

Einstein's affiliation with the Institute for Advanced Study would last until his death in 1955.[148] He was one of the four first selected (along with John von Neumann, Kurt Gödel, and Hermann Weyl[149]) at the new Institute. He soon developed a close friendship with Gödel; the two would take long walks together discussing their work. Bruria Kaufman, his assistant, later became a physicist. During this period, Einstein tried to develop a unified field theory and to refute the accepted interpretation of quantum physics, both unsuccessfully. He lived in Princeton at his home from 1935 onwards. The Albert Einstein House was made a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

World War II and the Manhattan Project

See also: Einstein–Szilárd letter Marble bust of Einstein at the Deutsches Museum in Munich

Marble bust of Einstein at the Deutsches Museum in Munich

In 1939, a group of Hungarian scientists that included émigré physicist Leó Szilárd attempted to alert Washington to ongoing Nazi atomic bomb research. The group's warnings were discounted. Einstein and Szilárd, along with other refugees such as Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, "regarded it as their responsibility to alert Americans to the possibility that German scientists might win the race to build an atomic bomb, and to warn that Hitler would be more than willing to resort to such a weapon."[150][151] To make certain the US was aware of the danger, in July 1939, a few months before the beginning of World War II in Europe, Szilárd and Wigner visited Einstein to explain the possibility of atomic bombs, which Einstein, a pacifist, said he had never considered.[152] He was asked to lend his support by writing a letter, with Szilárd, to President Roosevelt, recommending the US pay attention and engage in its own nuclear weapons research.

The letter is believed to be "arguably the key stimulus for the U.S. adoption of serious investigations into nuclear weapons on the eve of the U.S. entry into World War II".[153] In addition to the letter, Einstein used his connections with the Belgian royal family[154] and the Belgian queen mother to get access with a personal envoy to the White House's Oval Office. Some say that as a result of Einstein's letter and his meetings with Roosevelt, the US entered the "race" to develop the bomb, drawing on its "immense material, financial, and scientific resources" to initiate the Manhattan Project.

For Einstein, "war was a disease ... [and] he called for resistance to war." By signing the letter to Roosevelt, some argue he went against his pacifist principles.[155] In 1954, a year before his death, Einstein said to his old friend, Linus Pauling, "I made one great mistake in my life—when I signed the letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made; but there was some justification—the danger that the Germans would make them ..."[156] In 1955, Einstein and ten other intellectuals and scientists, including British philosopher Bertrand Russell, signed a manifesto highlighting the danger of nuclear weapons.[157] In 1960 Einstein was included posthumously as a charter member of the World Academy of Art and Science (WAAS),[158] an organization founded by distinguished scientists and intellectuals who committed themselves to the responsible and ethical advances of science, particularly in light of the development of nuclear weapons.

US citizenship

Einstein accepting a US citizenship certificate from judge Phillip Forman

Einstein accepting a US citizenship certificate from judge Phillip Forman

Einstein became an American citizen in 1940. Not long after settling into his career at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, he expressed his appreciation of the meritocracy in American culture compared to Europe. He recognized the "right of individuals to say and think what they pleased" without social barriers. As a result, individuals were encouraged, he said, to be more creative, a trait he valued from his early education.[159]

Einstein joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Princeton, where he campaigned for the civil rights of African Americans. He considered racism America's "worst disease",[131][160] seeing it as "handed down from one generation to the next".[161] As part of his involvement, he corresponded with civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois and was prepared to testify on his behalf during his trial as an alleged foreign agent in 1951.[162] When Einstein offered to be a character witness for Du Bois, the judge decided to drop the case.[163]

In 1946, Einstein visited Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, a historically black college, where he was awarded an honorary degree. Lincoln was the first university in the United States to grant college degrees to African Americans; alumni include Langston Hughes and Thurgood Marshall. Einstein gave a speech about racism in America, adding, "I do not intend to be quiet about it."[164] A resident of Princeton recalls that Einstein had once paid the college tuition for a black student.[163] Einstein has said, "Being a Jew myself, perhaps I can understand and empathize with how black people feel as victims of discrimination".[160]

Personal views

Political views

Main article: Political views of Albert Einstein Albert Einstein and Elsa Einstein arriving in New York in 1921. Accompanying them are Zionist leaders Chaim Weizmann (future president of Israel), Weizmann's wife Vera Weizmann, Menahem Ussishkin, and Ben-Zion Mossinson.

Albert Einstein and Elsa Einstein arriving in New York in 1921. Accompanying them are Zionist leaders Chaim Weizmann (future president of Israel), Weizmann's wife Vera Weizmann, Menahem Ussishkin, and Ben-Zion Mossinson.

In 1918, Einstein was one of the signatories of the founding proclamation of the German Democratic Party, a liberal party.[165][166] Later in his life, Einstein's political view was in favor of socialism and critical of capitalism, which he detailed in his essays such as "Why Socialism?".[167][168] His opinions on the Bolsheviks also changed with time. In 1925, he criticized them for not having a "well-regulated system of government" and called their rule a "regime of terror and a tragedy in human history". He later adopted a more moderated view, criticizing their methods but praising them, which is shown by his 1929 remark on Vladimir Lenin:

In Lenin I honor a man, who in total sacrifice of his own person has committed his entire energy to realizing social justice. I do not find his methods advisable. One thing is certain, however: men like him are the guardians and renewers of mankind's conscience.[169]

Einstein offered and was called on to give judgments and opinions on matters often unrelated to theoretical physics or mathematics.[140] He strongly advocated the idea of a democratic global government that would check the power of nation-states in the framework of a world federation.[170] He wrote "I advocate world government because I am convinced that there is no other possible way of eliminating the most terrible danger in which man has ever found himself."[171] The FBI created a secret dossier on Einstein in 1932; by the time of his death, it was 1,427 pages long.[172]

Einstein was deeply impressed by Mahatma Gandhi, with whom he corresponded. He described Gandhi as "a role model for the generations to come".[173] The initial connection was established on 27 September 1931, when Wilfrid Israel took his Indian guest V. A. Sundaram to meet his friend Einstein at his summer home in the town of Caputh. Sundaram was Gandhi's disciple and special envoy, whom Wilfrid Israel met while visiting India and visiting the Indian leader's home in 1925. During the visit, Einstein wrote a short letter to Gandhi that was delivered to him through his envoy, and Gandhi responded quickly with his own letter. Although in the end Einstein and Gandhi were unable to meet as they had hoped, the direct connection between them was established through Wilfrid Israel.[174]

Relationship with Zionism

Einstein in 1947

Einstein in 1947

Einstein was a figurehead leader in the establishment of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem,[175] which opened in 1925. Earlier, in 1921, he was asked by the biochemist and president of the World Zionist Organization, Chaim Weizmann, to help raise funds for the planned university.[176] He made suggestions for the creation of an Institute of Agriculture, a Chemical Institute and an Institute of Microbiology in order to fight the various ongoing epidemics such as malaria, which he called an "evil" that was undermining a third of the country's development.[177] He also promoted the establishment of an Oriental Studies Institute, to include language courses given in both Hebrew and Arabic.[178]

Einstein was not a nationalist and opposed the creation of an independent Jewish state.[179] He felt that the waves of arriving Jews of the Aliyah could live alongside existing Arabs in Palestine. The state of Israel was established without his help in 1948; Einstein was limited to a marginal role in the Zionist movement.[180] Upon the death of Israeli president Weizmann in November 1952, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion offered Einstein the largely ceremonial position of President of Israel at the urging of Ezriel Carlebach.[181][182] The offer was presented by Israel's ambassador in Washington, Abba Eban, who explained that the offer "embodies the deepest respect which the Jewish people can repose in any of its sons".[183] Einstein wrote that he was "deeply moved", but "at once saddened and ashamed" that he could not accept it.[183]

Religious and philosophical views

Duration: 1 minute and 31 seconds.

1:31

Opening of Einstein's speech (11 April 1943) for the United Jewish Appeal (recording by Radio Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina)"Ladies (coughs) and gentlemen, our age is proud of the progress it has made in man's intellectual development. The search and striving for truth and knowledge is one of the highest of man's qualities ..."

Main article: Religious and philosophical views of Albert Einstein

Einstein expounded his spiritual outlook in a wide array of writings and interviews.[184] He said he had sympathy for the impersonal pantheistic God of Baruch Spinoza's philosophy.[185] He did not believe in a personal god who concerns himself with fates and actions of human beings, a view which he described as naïve.[186] He clarified, however, that "I am not an atheist",[187] preferring to call himself an agnostic,[188][189] or a "deeply religious nonbeliever".[186] When asked if he believed in an afterlife, Einstein replied, "No. And one life is enough for me."[190]

Einstein was primarily affiliated with non-religious humanist and Ethical Culture groups in both the UK and US. He served on the advisory board of the First Humanist Society of New York,[191] and was an honorary associate of the Rationalist Association, which publishes New Humanist in Britain. For the 75th anniversary of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, he stated that the idea of Ethical Culture embodied his personal conception of what is most valuable and enduring in religious idealism. He observed, "Without 'ethical culture' there is no salvation for humanity."[192]

In a German-language letter to philosopher Eric Gutkind, dated 3 January 1954, Einstein wrote:

The word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses, the Bible a collection of honorable, but still primitive legends which are nevertheless pretty childish. No interpretation no matter how subtle can (for me) change this. ... For me the Jewish religion like all other religions is an incarnation of the most childish superstitions. And the Jewish people to whom I gladly belong and with whose mentality I have a deep affinity have no different quality for me than all other people. ... I cannot see anything 'chosen' about them.[193]

Einstein had been sympathetic toward vegetarianism for a long time. In a letter in 1930 to Hermann Huth, vice-president of the German Vegetarian Federation (Deutsche Vegetarier-Bund), he wrote:

Although I have been prevented by outward circumstances from observing a strictly vegetarian diet, I have long been an adherent to the cause in principle. Besides agreeing with the aims of vegetarianism for aesthetic and moral reasons, it is my view that a vegetarian manner of living by its purely physical effect on the human temperament would most beneficially influence the lot of mankind.[194]

He became a vegetarian himself only during the last part of his life. In March 1954 he wrote in a letter: "So I am living without fats, without meat, without fish, but am feeling quite well this way. It almost seems to me that man was not born to be a carnivore."[195]

Love of music

Einstein playing the violin (image published in 1927)

Einstein playing the violin (image published in 1927)

Einstein developed an appreciation for music at an early age. In his late journals he wrote:

If I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music ... I get most joy in life out of music.[196][197]

His mother played the piano reasonably well and wanted her son to learn the violin, not only to instill in him a love of music but also to help him assimilate into German culture. According to conductor Leon Botstein, Einstein began playing when he was 5. However, he did not enjoy it at that age.[198]

When he turned 13, he discovered the violin sonatas of Mozart, whereupon he became enamored of Mozart's compositions and studied music more willingly. Einstein taught himself to play without "ever practicing systematically". He said that "love is a better teacher than a sense of duty".[198] At the age of 17, he was heard by a school examiner in Aarau while playing Beethoven's violin sonatas. The examiner stated afterward that his playing was "remarkable and revealing of 'great insight'". What struck the examiner, writes Botstein, was that Einstein "displayed a deep love of the music, a quality that was and remains in short supply. Music possessed an unusual meaning for this student."[198]

Music took on a pivotal and permanent role in Einstein's life from that period on. Although the idea of becoming a professional musician himself was not on his mind at any time, among those with whom Einstein played chamber music were a few professionals, including Kurt Appelbaum, and he performed for private audiences and friends. Chamber music had also become a regular part of his social life while living in Bern, Zürich, and Berlin, where he played with Max Planck and his son, among others. He is sometimes erroneously credited as the editor of the 1937 edition of the Köchel catalog of Mozart's work; that edition was prepared by Alfred Einstein, who may have been a distant relation.[199][200]

In 1931, while engaged in research at the California Institute of Technology, he visited the Zoellner family conservatory in Los Angeles, where he played some of Beethoven and Mozart's works with members of the Zoellner Quartet.[201][202] Near the end of his life, when the young Juilliard Quartet visited him in Princeton, he played his violin with them, and the quartet was "impressed by Einstein's level of coordination and intonation".[198]

Death

On 17 April 1955, Einstein experienced internal bleeding caused by the rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, which had previously been reinforced surgically by Rudolph Nissen in 1948.[203] He took the draft of a speech he was preparing for a television appearance commemorating the state of Israel's seventh anniversary with him to the hospital, but he did not live to complete it.[204]

Einstein refused surgery, saying, "I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly."[205] He died in the Princeton Hospital early the next morning at the age of 76, having continued to work until near the end.[206]

During the autopsy, the pathologist Thomas Stoltz Harvey removed Einstein's brain for preservation without the permission of his family, in the hope that the neuroscience of the future would be able to discover what made Einstein so intelligent.[207] Einstein's remains were cremated in Trenton, New Jersey,[208] and his ashes were scattered at an undisclosed location.[209][210]

In a memorial lecture delivered on 13 December 1965 at UNESCO headquarters, nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer summarized his impression of Einstein as a person: "He was almost wholly without sophistication and wholly without worldliness ... There was always with him a wonderful purity at once childlike and profoundly stubborn."[211]

Einstein bequeathed his personal archives, library, and intellectual assets to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.[212]

Scientific career

Throughout his life, Einstein published hundreds of books and articles.[19][213] He published more than 300 scientific papers and 150 non-scientific ones.[16][213] On 5 December 2014, universities and archives announced the release of Einstein's papers, comprising more than 30,000 unique documents.[214][215] Einstein's intellectual achievements and originality have made the word "Einstein" synonymous with "genius".[11] In addition to the work he did by himself he also collaborated with other scientists on additional projects including the Bose–Einstein statistics, the Einstein refrigerator and others.[216][217]

There is some evidence from Einstein's writings that he collaborated with his first wife, Mileva Marić. In 13 December 1900, a first article on capillarity signed only under his name was submitted. The decision to publish only under his name seems to have been mutual, but the exact reason is unknown.[38]

1905 – Annus Mirabilis papers

The Annus Mirabilis papers are four articles pertaining to the photoelectric effect (which gave rise to quantum theory), Brownian motion, the special theory of relativity, and E = mc2 that Einstein published in the Annalen der Physik scientific journal in 1905. These four works contributed substantially to the foundation of modern physics and changed views on space, time, and matter. The four papers are:

Title (translated)Area of focusReceivedPublishedSignificance"On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light"[218]Photoelectric effect18 March9 JuneResolved an unsolved puzzle by suggesting that energy is exchanged only in discrete amounts (quanta).[219] This idea was pivotal to the early development of quantum theory.[220]"On the Motion of Small Particles Suspended in a Stationary Liquid, as Required by the Molecular Kinetic Theory of Heat"[221]Brownian motion11 May18 JulyExplained empirical evidence for the atomic theory, supporting the application of statistical physics."On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies"[222]Special relativity30 June26 SeptemberReconciled Maxwell's equations for electricity and magnetism with the laws of mechanics by introducing changes to mechanics, resulting from analysis based on empirical evidence that the speed of light is independent of the motion of the observer.[223] Discredited the concept of a "luminiferous ether".[224]"Does the Inertia of a Body Depend Upon Its Energy Content?"[225]Matter–energy equivalence27 September21 NovemberEquivalence of matter and energy, E = mc2, the existence of "rest energy", and the basis of nuclear energy.

Statistical mechanics

Thermodynamic fluctuations and statistical physics

Main articles: Statistical mechanics, thermal fluctuations, and statistical physics

Einstein's first paper[77][226] submitted in 1900 to Annalen der Physik was on capillary attraction. It was published in 1901 with the title "Folgerungen aus den Capillaritätserscheinungen", which translates as "Conclusions from the capillarity phenomena". Two papers he published in 1902–1903 (thermodynamics) attempted to interpret atomic phenomena from a statistical point of view. These papers were the foundation for the 1905 paper on Brownian motion, which showed that Brownian movement can be construed as firm evidence that molecules exist. His research in 1903 and 1904 was mainly concerned with the effect of finite atomic size on diffusion phenomena.[226]

Theory of critical opalescence

Main article: Critical opalescence

Einstein returned to the problem of thermodynamic fluctuations, giving a treatment of the density variations in a fluid at its critical point. Ordinarily the density fluctuations are controlled by the second derivative of the free energy with respect to the density. At the critical point, this derivative is zero, leading to large fluctuations. The effect of density fluctuations is that light of all wavelengths is scattered, making the fluid look milky white. Einstein relates this to Rayleigh scattering, which is what happens when the fluctuation size is much smaller than the wavelength, and which explains why the sky is blue.[227] Einstein quantitatively derived critical opalescence from a treatment of density fluctuations, and demonstrated how both the effect and Rayleigh scattering originate from the atomistic constitution of matter.

Special relativity

Main article: History of special relativity

Einstein's "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper"[222] ("On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies") was received on 30 June 1905 and published 26 September of that same year. It reconciled conflicts between Maxwell's equations (the laws of electricity and magnetism) and the laws of Newtonian mechanics by introducing changes to the laws of mechanics.[228] Observationally, the effects of these changes are most apparent at high speeds (where objects are moving at speeds close to the speed of light). The theory developed in this paper later became known as Einstein's special theory of relativity.

This paper predicted that, when measured in the frame of a relatively moving observer, a clock carried by a moving body would appear to slow down, and the body itself would contract in its direction of motion. This paper also argued that the idea of a luminiferous aether—one of the leading theoretical entities in physics at the time—was superfluous.[note 4]

In his paper on mass–energy equivalence, Einstein produced E = mc2 as a consequence of his special relativity equations.[229] Einstein's 1905 work on relativity remained controversial for many years, but was accepted by leading physicists, starting with Max Planck.[note 5][230]

Einstein originally framed special relativity in terms of kinematics (the study of moving bodies). In 1908, Hermann Minkowski reinterpreted special relativity in geometric terms as a theory of spacetime. Einstein adopted Minkowski's formalism in his 1915 general theory of relativity.[231]

General relativity

General relativity and the equivalence principle

Main article: History of general relativity

See also: Theory of relativity and Einstein field equations Eddington's photograph of a solar eclipse

Eddington's photograph of a solar eclipse

General relativity (GR) is a theory of gravitation that was developed by Einstein between 1907 and 1915. According to it, the observed gravitational attraction between masses results from the warping of spacetime by those masses. General relativity has developed into an essential tool in modern astrophysics; it provides the foundation for the current understanding of black holes, regions of space where gravitational attraction is so strong that not even light can escape.[232]

As Einstein later said, the reason for the development of general relativity was that the preference of inertial motions within special relativity was unsatisfactory, while a theory which from the outset prefers no state of motion (even accelerated ones) should appear more satisfactory.[233] Consequently, in 1907 he published an article on acceleration under special relativity. In that article titled "On the Relativity Principle and the Conclusions Drawn from It", he argued that free fall is really inertial motion, and that for a free-falling observer the rules of special relativity must apply. This argument is called the equivalence principle. In the same article, Einstein also predicted the phenomena of gravitational time dilation, gravitational redshift and gravitational lensing.[234][235]

In 1911, Einstein published another article "On the Influence of Gravitation on the Propagation of Light" expanding on the 1907 article, in which he estimated the amount of deflection of light by massive bodies. Thus, the theoretical prediction of general relativity could for the first time be tested experimentally.[236]